Our Featured Artist for March 2021

Neal Brantley

Neal Brantley grew up in Troy in an artistic household: his mother, Jane Brantley, was a painter. In 1966, as a sophomore in high school, he began taking private lessons from Troy State Art professor Alice Thornton, who taught watercolor. Neal enrolled at Auburn University for two years and then transferred to Tulane University where he graduated in 1973 with a BFA in Painting.

His first solo exhibit was in 1979 in New Orleans at Diversity’s Gallery in the French Quarter: the theme of that show was Mardi Gras. Brantley found New Orleans to be a city appreciative of art. Since that time his paintings have evolved in style and subject. Large cityscapes brought him success, but he was not content to rest on his laurels. The artist is an engaged intellect, he is curious, and as he possesses a questioning and fearless nature, he continues to expand his oeuvre. Several recent works are landscapes which include a unique or interesting structure.

His medium is oil paint, the paint of the old masters and great modernists, among them Rembrandt (1606-1669) and Van Gogh (1853-1890). Brantley paints in layers, a traditional way of applying oil paint. When one-layer dries, he then puts another layer on top; the resulting surfaces are beautiful, softened areas seem to float on the surface of the canvas, especially visible in the artist’s landscapes.

His work is in several permanent collections, among them: The Louisiana State Museum in New Orleans, Tulane University, The Retirement Systems of Alabama, The Jackson Hospital Foundation in Montgomery, and the City of Troy. Private collections of his work are also in Chicago, Atlanta and New Orleans.

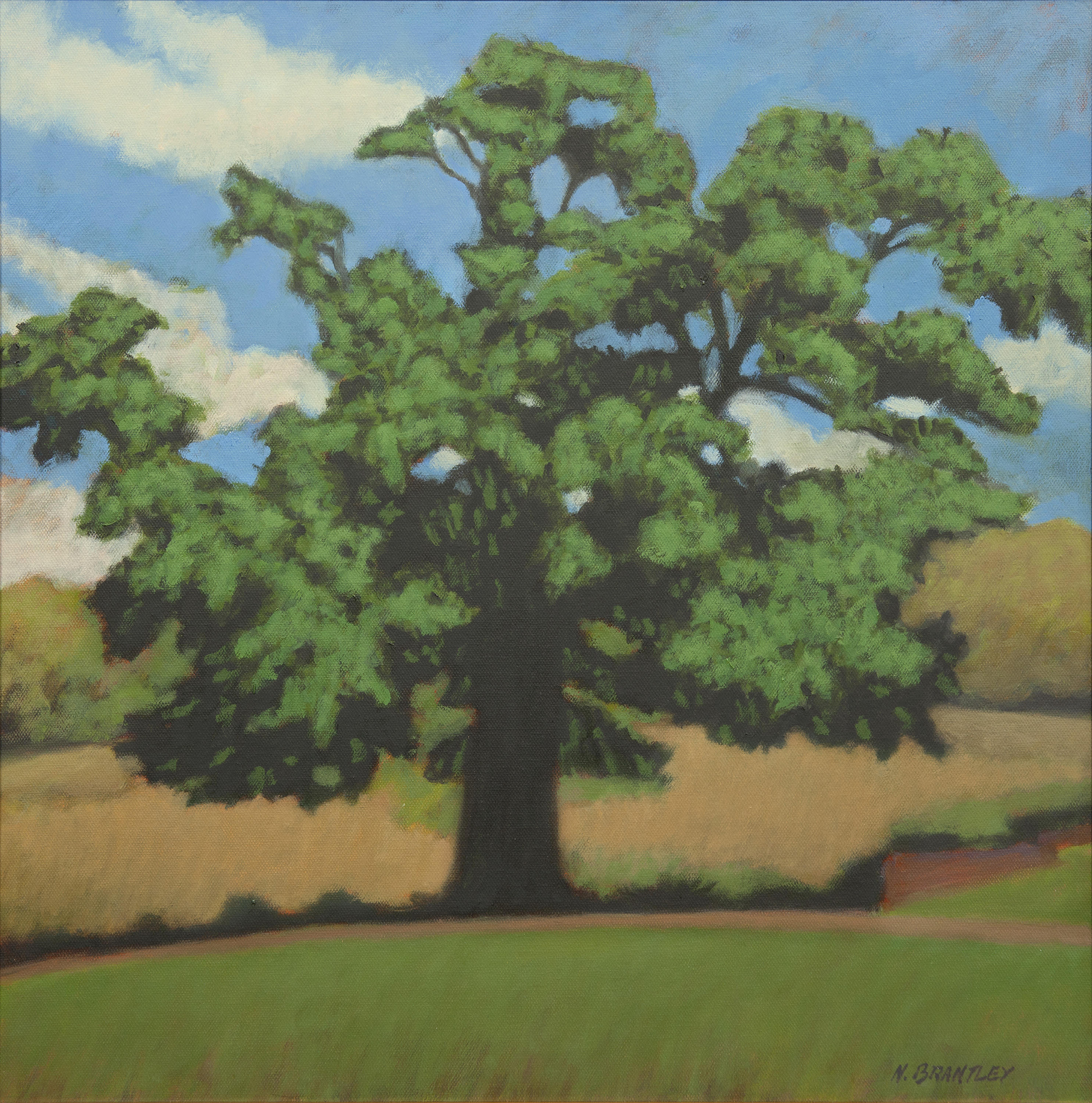

I especially love two paintings of trees: Gingko Tree and Southern Oak. The gingko is undergoing abscission; the deciduous tree stops making food as the seasons change, the golden color was always there, masked by green; as the green breaks down, the gold emerges—that is what we see here. All aspects come together here: the break in the curb halts the diagonal in the asymmetrical composition, the movement is not present, but implied: the leaves have fallen, more will fall. We are caught up in a moment of change—of transformation—as the tree prepares for winter—a time for renewal.

As for the oak, Brantley remembers that it was the striking dark value which first caught his eye, he recalls that there was no three-dimensional quality in the darkest darks—they were simply flat. In this rather remarkable composition, the tree fills the square canvas, its structure but a pattern against a flattened horizon. Yet clouds float diagonally in an intensely blue sky.

Brantley’s cityscapes appear, at first glance, static and unmoving—but look again. Examining French Quarter Rooftops, the viewer’s eye is first drawn to the to a slightly off-center vertical, a large modern structure is behind the older buildings; but the eye continues to move in oblique angles, outward toward the foreground, then back toward the middle ground following the edges of the rooftops. The painting is full of movement.

The painting also offers a key to understanding the artist’s oeuvre: the artist’s point of view is one of the most important aspects of Brantley’s work. It would be virtually impossible to reproduce this painting because it is a narrow view from a small balcony at a given moment in time; captured alone by the artist.

In East River Sunrise, New York, a tall office building on the left side of the painting is impersonal—nameless individuals work there—some are working at this moment. On the right side of the painting a pair of smaller buildings may be apartments—curtains at the upper windows indicate human presence—the personal aspect is contrasted with the impersonal. Brantley is a highly sophisticated colorist—he mixes all of his colors—his chromatic grays are a source of great pleasure. Chromatic grays are made by mixing warm and cool colors—they are not simply made by adding light pigment to dark pigment. Chromatic grays rich with violet and green depth make East River Sunrise, New York a great painting.

The artist reminded me that Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) painted several East River landscapes when she lived in New York. He admires O’Keeffe and her straightforward response to comments made by others about her work: “I decided I was a very stupid fool not to at least paint as I wanted to and to say what I wanted to when I painted as that seemed to be the only thing I could do that didn’t concern anybody but myself—that was nobody’s business but my own.”

The dimensions of The Town of Spectre, a long horizontal painting, suggests that something is different about the landscape. It is a world created then abandoned, existing as a curiosity. There is something mysterious and ghostlike about the work. Brantley recalls that Alfred Hitchcock was once asked, “What is the mystery here?” He replied, “If you knew, then it wouldn’t be a mystery.”

Look closely at Brantley’s paintings: the softness in brush strokes is compelling. Look at his clouds—they are always a compositional element, but also an expressive force. Let his color speak to you as it does in two paintings very different in subject matter. Both works are striking examples of descriptive and expressive color. Brantley mixed his color repeatedly to get the salmon tone of the building in Dauphine Street, New Orleans which is contrasted with gray-green of the shutters. It’s a subtle, yet exquisite relationship. West Bound on South Street seems like an ordinary everyday scene—we might see it and let it pass—but the artist sees the tracks in the sky and the back of an automobile, a neutral foreground, middle ground, and background. He notices one thing: the taillights on the vehicle are the same color as the sunset. What was an ordinary observation is now a painting. Because of this unexpected connection we see the world a little differently.

Curious, I asked Brantley if there was metaphorical or philosophical aspect to some of his imagery. He replied that that was in his subconscious, not in his conscious mind. I shared with Brantley an observation made by Henri Poincare (1854-1912) “the subliminal self is in no way inferior to the conscious self: it is not purely automatic, it has tact, delicacy; it knows how to choose, to divine.” I look forward to future talks with the artist about the subluminal aspects of his work

Neal Brantley’s work is rich with beauty, promise, and understanding. He is an artist I respect and writing about his work is a pleasure. Enjoy these paintings.

Susan Hood, PhD

Contact

Richard Metzger, Gallery Director

- email us here

- 334-262-8256

401 Cloverdale RD Montgomery AL 36106

334-262-8256